I kind of feel I should just leave it there. But no, I won't.

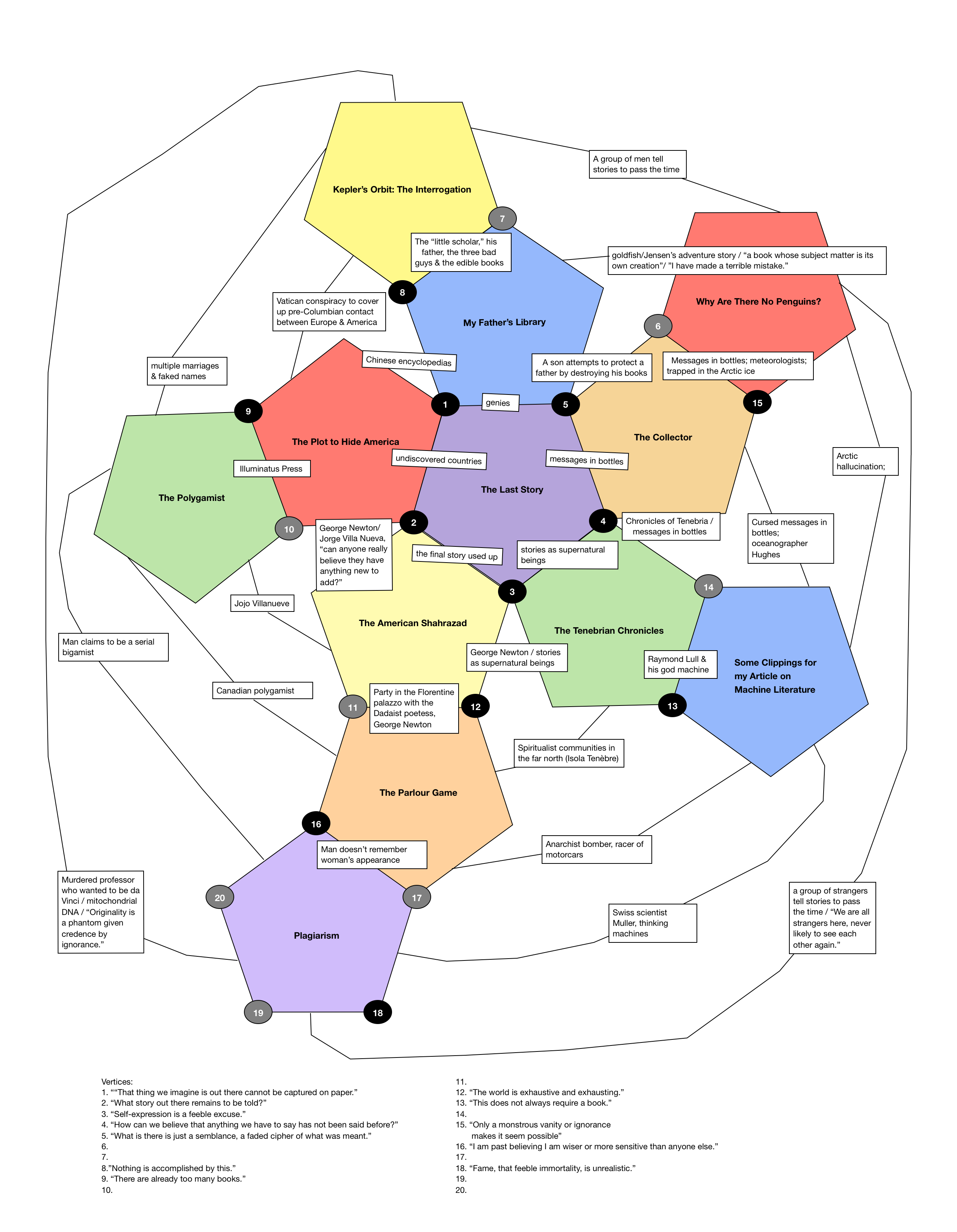

I had good fun with Paul Glennon's The Dodecahedron. This series of twelve interlinked stories, structured like a dodecahedron in which each shares five referential "sides" with its contiguous stories, and thrice-repeated phrases create "vertices" among story-triads, functions like a giant Sudoku puzzle and kept me reaching for my pen and subsequently for my computer to track the appearances and reappearances of various motifs. While Glennon's stories are more clever and stylized than affective or deep, more of an ingenious game than Kafka's "axe for the frozen sea within," I still found The Dodecahedron to be a thoroughly enjoyable little excursion into literary geometry. The overarching interest and suspense, for me, came not from the individual stories themselves but from watching their interrelationships tug and rearrange themselves, seeming to fall into place in one story only to be brought into question in the next.

Indeed, one of the most interesting things about Glennon's highly structured book is the number of places that structure seems in danger of collapsing in on itself. Sometimes, as in "The Parlor Game" and "Some Clippings on My Article on Machine Literature," this happens in a way that almost feels like "cheating": it is easier, after all, to incorporate references to five other stories into the story you're writing if you use a kind of clip show format. In general, I found the stories stronger toward the beginning of the book because of just this phenomenon. In many cases, though, I liked the ambiguity created by the way Glennon's ostensibly geometric formations don't quite fit together, like a door sticking in its jamb. The stories often echo each other without mapping precisely one onto the next; the ones that come later in the book don't necessarily "explain" the ones that come earlier.

Throughout the collection, for example, there is a recurring theme of a young boy whose father is missing, and the three shadowy strangers who are searching for him. Variations on this basic plot resurface again and again. One expects them to resolve at some point, but they never truly do: is the narrator of "My Father's Library" merely the protagonist of the adventure novel written by Jensen in "Why Are There No Penguins?" Is the Arctic explorer in that story merely hallucinating Jensen's novel, or did he hallucinate his entire previous life based on something Jensen once told him? Is the "Why Are There No Penguins" narrator the Ulrich Gjedson mentioned in "The Collector"? If so, the details don't exactly fit: a seemingly analogous character is at one point named "Jenkins," elsewhere "Jensen"—and in one case he dies by fever, in another by poison. Similarly, another character is "Katerina" in one story, "Catherine" elsewhere. Even the repeated phrases at the vertices occasionally refuse to match up exactly, so that we get "self-expression is a feeble excuse" ("The American Shahrazad"); "wish-fulfillment, like self-expression, is a feeble excuse" ("The Tenebrian Chronicles"); and "Self-expression and self-exploration are feeble excuses" ("The Last Story"). In this last example, the addition of "and self-exploration" is not required by the story; it would have been easy enough for all of the phrases to match exactly, but Glennon appears to insist on a strong, yet inexact, correlation.

The strength of the narrative echoes sometimes build up to a point where they compromise or disguise Glennon's laboriously-built scaffolding. The plots of young boys protecting their imperiled fathers, for example, and the theme of pre-Columbian contact between American and Europe, crop up in so many of these stories that their appearance can no longer be taken to signal anything about the collection's geometry: they spread among non-adjacent stories throughout the book. It can therefore sometimes be difficult to find the key "connection" between two stories, even if they have MANY obvious connections, if those same connections crop up too often elsewhere. The journalist narrator of "The Plot to Hide America" writes that

Connecting the four stories was a small miracle, but nothing about it is reassuring. The sheer luck of it makes me doubt my own profession. I'm reminded of how many stories are out there undiscovered. Even when the characters and events are known to everyone, luck has to intervene to assemble the story. It convinces me that for every story we chance to put together, thousands of others remain disassembled and lost. For every person like myself with an interest in reintegrating distant facts into a coherent story, there are many others who would prefer to keep those facts scattered and confused. It reminds me that there are people working to assure that the thing we imagine is out there cannot be captured on paper.

But Glennon's work also suggests the opposite problem: that when the human mind is looking for connections, looking to "reintegrate distant facts into a coherent story," it's apt to find those connections even when they don't exist. Or, when the mind starts finding legitimate connections between two things, it will then find more and more until it can't distinguish which connections are the important ones, and which irrelevant. So too, connections in Glennon's book are just as likely to call into question their earlier incarnations, as they are to reinforce them. Little, as the journalist says, that is "reassuring," except the fun of assembling and disassembling narratives as connections come and go.

The Dodecahedron was the April pick for The Wolves reading group. Since I'll be in France for our May discussion dates, and probably blogging like mad about the trip, I'm not positive whether or not I'll be able to participate at the same time as everyone else. Still, I am very excited about Frances's pick, so you should all join in the discussion of Gabriel Josipovici's What Ever Happened to Modernism? on the last weekend of the month.

PS: Did anyone else find the vertices I'm missing? (You can click to enlarge, in case that wasn't clear.)

I Iove that you mapped the dodecahedron, Emily. You went one step further than me, though at one early point I shared the intention. A week or so after finishing the book, the glow has not survived. I am glad I read the book, but more as an interesting intellectual exercise. The book has a future as a study for a creative writing class.

I got a little bit obsessed with the mapping. By the end it was getting in the way of really enjoying the stories, actually.

I think "intellectual exercise" is right. Not affective or tremendously long-lasting, but enjoyable in the moment and as a brain-puzzle.

I'm into frames at the moment because I turn out to be in love with Willa Cather who is all about the frame. When I taught and read a lot of French experimental fiction I was also into intellectual puzzle texts; but that's kind of trailed off a bit now. I'm not sure whether this would land in the fascinating middle ground between frames and puzzles, or whether it would be not enough frame and too much puzzle and I would feel critical of its lack of heart. But it does sound very intriguing! I'm hoping to join in on the Josipovici reading, if that's okay,so I'm really sorry if you won't be there. But then- France! How lovely! I hope you have a wonderful time.

Please do join for Josipovici, Litlove! I think it will be a really good discussion. It's possible I will be there, but I don't want to stress about it so I'm giving myself an out. :-)

I wouldn't have thought of Cather as particularly frame-heavy, but now that you mention it, she certainly is, isn't she? As far as Glennon, I think it is lacking in heart, but if you go into it with that expectation I think it's pretty successful at being what it is - an intellectually interesting meditation on different perspectives and how they fit and don't quite fit together.

what an interesting story collection with such complex interlocking stories love the diagram ,all the best stu

Thanks, Stu! The complex interlocking aspect was pretty much what made this book for me. And the excuse to make a diagram. :-)

Your review is much more positive than the review I read of this book earlier in the week elsewhere.

I can see what you mean about the puzzle aspects of the book tending to overwhelm the story aspects, but I can also see that the puzzle itself may be worth the time it takes to read the book. It sounds like something I might enjoy, maybe a good summertime read.

Haha, I bet I can guess where that other review might have been. ;-)

I think if you go in expecting it to be very puzzle-heavy, rather than an emotional or soulful collection, it's likely to be fun for you. The stories themselves are very quick-reading; I'd say summertime reading is a good call.

Emily, your post and in particular that crazy-ass diagram of yours are fascinating and fun by turns. How ironic then that I found Glennon's book so utterly non-fascinating and non-fun myself. In fact, I would have stopped after the first story if this hadn't been a Wolves read. Woulda, coulda, shoulda, I know. Cheers!

LOL, well I'm glad that at least you got some enjoyment out of my crazy-ass diagram, Richard, even if you hated the book! :-)

I'm floored by your diagram - it's even more awesome than I had hoped. I almost want to print it out and hang it on my wall. :)

I love what you say about connections there at the end of your post. The way the details effected other aspects of other stories so unpredictably was cool, and being left in the end totally unsure of what, if anything, had actually happened in the book was a different (and welcome) reading experience for me.

Haha, I'm glad I surpassed your expectations, Sarah! :-) And yes, I definitely agree about the level of details affecting one's perceptions of other stories throughout the reading experience - so much fun how Glennon avoids a "definitive" interpretation. Well chosen!

You are the source of many interesting books! I think I might like this one, especially going into it knowing a little of what to expect (an intellectual challenge, not much heart). I love your diagram, and I'm glad to know it's there in case I do read this book and want some help with it :)

Yes, I really think going into it with the expectation of a puzzle with much cleverness and little heart would give the best potential for enjoyment here. If that's what you're in the mood for, though, it's a great little adventure! :-)

You made an entire chart! That is so awesome.

As you know I loved this one and can only conclude that Richard is on drugs. Since all he could do was rant about how much he hated this book, I much appreciate your intelligent, well thought-out critiques.

I especially liked your last paragraph about how the human mind consciously looks for patterns. (Similar to how our brain is designed to see faces in random visual patterns. I discerned a face on a tree truck the other day.) That really does lend another element of instability to the book's in-universe reality. In fact, that's how conspiracies arise - from perceived patterns.

I am a serious pattern-finder, ever since I was a tiny kid, so the pattern-finding aspect of this book was right up my alley. Could not resist the allure of the chart. :-) So true that the unreliability of pattern-spotting adds yet another layer of instability to the book's universe.

I love your diagram! When I first read this book, years ago, I'd started doing exactly that, but never got around to writing about it the way I wanted to. I can't put my finger on why I like this book — something about it just resonates with me, even though I see that it's not especially deep, but it's fun. I so wanted to reread this with everybody this month but life got in the way. Hopefully I'll find time soon. I'm printing out your chart to match up with my old notes.

Haha, glad the diagram is helping people out, Isabella. Maybe your old notes can help identify some of the vertices I'm missing! I thought about you a lot while reading this, and the way you got involved with the geometry in Life a User's Manual—I didn't really follow the progress around the apartment building in that book but I definitely got into it here. :-)

What a curious and fascinating book! I don't think I'll ever read it but I enjoyed reading about your reading of it and the diagram! I think I am more impressed by the diagram than I am about the book :)

I feel so vindicated by all of this love for my diagram. :-) Yeah, the book itself is, I think, very appealing for an extremely narrow range of moods, and maybe even narrow range of readers. It happened to hit me at exactly the right time, though, so I thought it was a kick.

Wow! Your diagram is so much better than that fucking book that I wish I had just read that instead. The book, in my opinion, was not close to collapsing in on itself. It did collapse. And then to have to explain its own structure at close? I had to audible my displeasure over that one. Loudly. So again with the sharply divergent opinions this month. :) Come on May!

It's fun when we all like a book, but on the other hand it makes total sense that it's unusual given how odd/experimental some of our choices and our "no re-reads" policy (i.e., no vetting beforehand). And I think it's pretty fascinating to see where opinions on different works break down—I can never predict who will love which books, even after a few years of reading together.

Too bad you didn't like this one but I bet Richard will welcome the company. ;-)