I kind of feel I should just leave it there. But no, I won't.

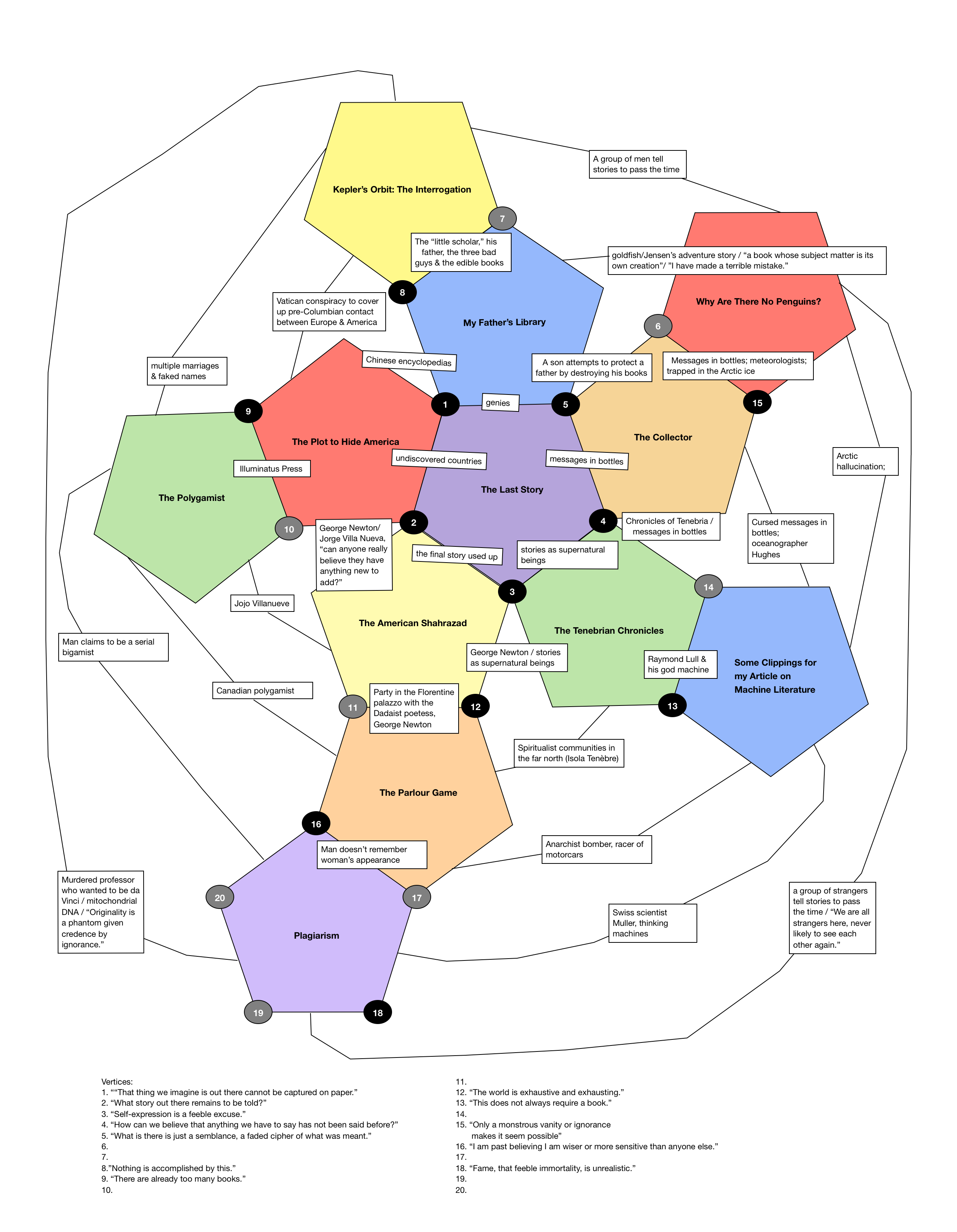

I had good fun with Paul Glennon's The Dodecahedron. This series of twelve interlinked stories, structured like a dodecahedron in which each shares five referential "sides" with its contiguous stories, and thrice-repeated phrases create "vertices" among story-triads, functions like a giant Sudoku puzzle and kept me reaching for my pen and subsequently for my computer to track the appearances and reappearances of various motifs. While Glennon's stories are more clever and stylized than affective or deep, more of an ingenious game than Kafka's "axe for the frozen sea within," I still found The Dodecahedron to be a thoroughly enjoyable little excursion into literary geometry. The overarching interest and suspense, for me, came not from the individual stories themselves but from watching their interrelationships tug and rearrange themselves, seeming to fall into place in one story only to be brought into question in the next.

Indeed, one of the most interesting things about Glennon's highly structured book is the number of places that structure seems in danger of collapsing in on itself. Sometimes, as in "The Parlor Game" and "Some Clippings on My Article on Machine Literature," this happens in a way that almost feels like "cheating": it is easier, after all, to incorporate references to five other stories into the story you're writing if you use a kind of clip show format. In general, I found the stories stronger toward the beginning of the book because of just this phenomenon. In many cases, though, I liked the ambiguity created by the way Glennon's ostensibly geometric formations don't quite fit together, like a door sticking in its jamb. The stories often echo each other without mapping precisely one onto the next; the ones that come later in the book don't necessarily "explain" the ones that come earlier.

Throughout the collection, for example, there is a recurring theme of a young boy whose father is missing, and the three shadowy strangers who are searching for him. Variations on this basic plot resurface again and again. One expects them to resolve at some point, but they never truly do: is the narrator of "My Father's Library" merely the protagonist of the adventure novel written by Jensen in "Why Are There No Penguins?" Is the Arctic explorer in that story merely hallucinating Jensen's novel, or did he hallucinate his entire previous life based on something Jensen once told him? Is the "Why Are There No Penguins" narrator the Ulrich Gjedson mentioned in "The Collector"? If so, the details don't exactly fit: a seemingly analogous character is at one point named "Jenkins," elsewhere "Jensen"—and in one case he dies by fever, in another by poison. Similarly, another character is "Katerina" in one story, "Catherine" elsewhere. Even the repeated phrases at the vertices occasionally refuse to match up exactly, so that we get "self-expression is a feeble excuse" ("The American Shahrazad"); "wish-fulfillment, like self-expression, is a feeble excuse" ("The Tenebrian Chronicles"); and "Self-expression and self-exploration are feeble excuses" ("The Last Story"). In this last example, the addition of "and self-exploration" is not required by the story; it would have been easy enough for all of the phrases to match exactly, but Glennon appears to insist on a strong, yet inexact, correlation.

The strength of the narrative echoes sometimes build up to a point where they compromise or disguise Glennon's laboriously-built scaffolding. The plots of young boys protecting their imperiled fathers, for example, and the theme of pre-Columbian contact between American and Europe, crop up in so many of these stories that their appearance can no longer be taken to signal anything about the collection's geometry: they spread among non-adjacent stories throughout the book. It can therefore sometimes be difficult to find the key "connection" between two stories, even if they have MANY obvious connections, if those same connections crop up too often elsewhere. The journalist narrator of "The Plot to Hide America" writes that

Connecting the four stories was a small miracle, but nothing about it is reassuring. The sheer luck of it makes me doubt my own profession. I'm reminded of how many stories are out there undiscovered. Even when the characters and events are known to everyone, luck has to intervene to assemble the story. It convinces me that for every story we chance to put together, thousands of others remain disassembled and lost. For every person like myself with an interest in reintegrating distant facts into a coherent story, there are many others who would prefer to keep those facts scattered and confused. It reminds me that there are people working to assure that the thing we imagine is out there cannot be captured on paper.

But Glennon's work also suggests the opposite problem: that when the human mind is looking for connections, looking to "reintegrate distant facts into a coherent story," it's apt to find those connections even when they don't exist. Or, when the mind starts finding legitimate connections between two things, it will then find more and more until it can't distinguish which connections are the important ones, and which irrelevant. So too, connections in Glennon's book are just as likely to call into question their earlier incarnations, as they are to reinforce them. Little, as the journalist says, that is "reassuring," except the fun of assembling and disassembling narratives as connections come and go.

The Dodecahedron was the April pick for The Wolves reading group. Since I'll be in France for our May discussion dates, and probably blogging like mad about the trip, I'm not positive whether or not I'll be able to participate at the same time as everyone else. Still, I am very excited about Frances's pick, so you should all join in the discussion of Gabriel Josipovici's What Ever Happened to Modernism? on the last weekend of the month.

PS: Did anyone else find the vertices I'm missing? (You can click to enlarge, in case that wasn't clear.)