Recently, I don't know why, I've been taken by a sudden and overwhelming craving for Shakespeare. It could be all the Montaigne, I suppose; having not read Shakespeare at all since finishing my undergrad thesis on King Lear and Montaigne's "Of Experience," the self-effacing humanism of the one has me coveting the richness and textured diction of the other. In any case, I decided on a whim to start at the compositional beginning: with the three Shakespearean plays first performed (1590-92), Henry VI, Parts One and Two.

The compositional beginning is, of course, not the chronological beginning. Henry VI Part 1 opens on a kingdom in disarray: the strong old king, Henry V (whose earlier incarnations as Prince Hal and Henry V Shakespeare would go on to portray later in his career) has just died, leaving an underage son and a political vacuum of which literally everyone and their cousin is rushing to take ownership. And what a bunch of vile cousins they are. The Duke of Gloster, the official Protector of young Henry VI and one of the only truly sympathetic characters, is at odds with Cardinal Beaufort, a Wolsey-esque figure attempting to rule the kingdom from the Church seat. In Part 1 we get the famous scene of discord between the Duke of Somerset and Richard Plantagenet (later the Duke of York) which establishes the red rose as the badge of the house of Lancaster and the white rose as the badge of the house of York, and presages the bloody Wars of the Roses to follow. On top of all this, the Duke of Suffolk is attempting to curry favor with the King by convincing Henry to marry the woman of Suffolk's choice—Princess Margaret, through whom Suffolk himself hopes to rule by proxy. A Better Book Titles-style renaming of this trilogy might be, Too Many Dukes! (And Also A Surfeit of Earls).

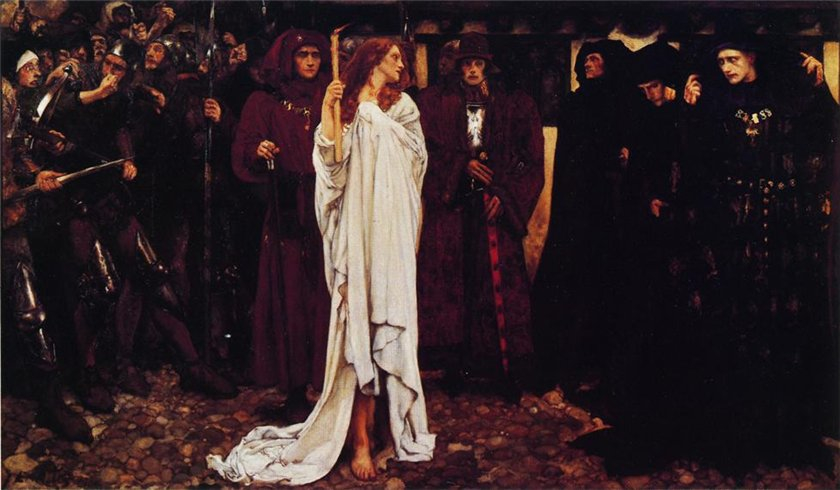

And indeed, in the Henry VI plays one can see the beginning of a Shakespearean obsession: the danger inherent in a divided kingdom or house, in having too many cooks in the kitchen. However revolutionary he was in a lingual sense, Shakespeare was a political conservative; in his mind, a country lacking a single, strong and legitimate monarch was in serious trouble. This is especially true when a whole court is distracted from an outside threat; in this case, the infighting comes at a particularly unfortunate time, because England is currently at war with France, and the French army has just acquired the secret weapon in the form of Joan of Arc. While the French find new purchase thanks to Joan's galvanic leadership (and conjuration of demons), the English let their petty rivalries keep them from sending reinforcements into battle, thus jeopardizing one of their most experienced and honorable commanders. In fact, it's usually the nice guys who finish last when dueling dukes get going:

DUKE OF GLOSTER

Ah, gracious lord, these days are dangerous!

Virtue is choked with foul ambition,

And charity chased hence by rancour's hand;

Foul subornation is predominant,

And equity exiled in your highness' land.

I know their complot is to have my life;

And, if my death might make this island happy,

And prove the period of their tyranny,

I would expend it with all willingness:

But mine is made the prologue to their play;

For thousands more, that yet suspect no peril,

Will not conclude their plotted tragedy.

(In this speech we see a hint of another typically Shakespearean practice more famous in Hamlet, Midsummer Night's Dream, and As You Like It: the tendency to use imagery of plays and actors within the plays themselves, creating a nesting-boxes effect. "Plotted tragedy" is a nice pun on "plotting" as in scheming, and "plotting" as in planning out the events of a story or drama.)

That problem of legitimacy is a tough nut in the Henry VI plays—much more so than in some other Shakespeare works, because, at least at first, the "rightful" succession isn't clear. Often, when there is a cold-blooded and manipulative usurper in Shakespeare, like Richard III or Hamlet's Claudius, that person is clearly marked out as a villain, while the rightful heir to the throne is de facto morally righteous. Reluctant or "weak" usurpers, like Macbeth, are perhaps a more complicated case—their character fails them, despite their qualms. But in Henry VI, we have in Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York a clear-headed, manipulative character who is attempting to arrange events to topple the current king; yet Shakespeare hesitates to portray the Duke of York as a complete villain—unsurprising, since his claim to the throne is actually stronger than Henry's. Throughout Part 1, it's as if all the characters are struggling through a moral fog: everyone has his set of allegiances, but all sides are morally equal, equally self-serving. One could equally well come to the conclusion that one person is the rightful king, as that another is. As Salisbury says late in Part 2, "It is a great sin to swear unto a sin; / But greater sin to keep a sinful oath." In such a catch-22 situation, there's really no easy way to stick to one's guns and feel secure in one's virtue: a surprisingly nihilistic vision for the first plays by a man who often shows himself a staunch monarchist.

As this fog coalesces around the Duke of York and his claims to be the rightful heir to the throne in Part 2, Shakespeare grapples with the question of whether a plot against the crown is ever justified: what creates "legitimacy"? Henry VI is the grandson of a usurper, and York's line of descent is closer than Henry's, so if legitimacy is a marker of Divine Right to Rule, the crown should go to York. Yet Henry is the lawful son of the previous king, who was himself the lawful son of the king before that, not to mention that he's already sitting on the throne—so if legitimacy is a practical device for ensuring stability in the realm, the crown should stay with Henry. Though again, if it is a simple practicality in the service of stability, leaving the crown to Henry may not be the best idea after all, given the young king's gullible, easy-going nature in this time of war. Is York, then, justified in intentionally undermining Henry's rule? If he is justified, is it because of his lineage, or because of Henry's weakness as a monarch? His behavior looks from the outside exactly like a treasonous plot. Is there any difference, especially when he sacrifices virtuous people in order to gain his ends? And when he makes such delicious yet devious speeches as this?

DUKE OF YORK

Well, nobles, well, 'tis politicly done,

To send me packing with a host of men;

I fear me you but warm the starved snake,

Who, cherisht in your breasts, will sting your hearts.

'Twas men I lackt, and you will give them me;

I take it kindly; yet be well assured

You put sharp weapons in a madman's hands.

Whiles I in Ireland nourish a mighty band,

I will stir up in England some black storm,

Shall blow ten thousand souls to heaven or hell;

And this fell tempest shall not cease to rage

Until the golden circuit on my head,

Like to the glorious sun's transparent beams,

Do calm the fury of this mad-bred flaw.

It's hard to think that York is as admirable as Gloster; on the other hand, he's certainly no more despicable than Suffolk, Somerset, Beaufort, or any of the other schemers and plotters. Does his noble(r) birth alone elevate him above their level? One wonders if the answers to these moral questions are, for Shakespeare, at all dependent on outcome: had Richard Plantagenet succeeded in his bid for kingship, rather than merely touching off the powder keg that became the Wars of the Roses and siring the villain who would become Richard III, would they have been justified by the end result of returning the legitimate heir to the throne? Particularly in a time of war, an argument has often been made that ends justify means; and it's just possible that York himself believes that restoring the golden circuit to his own head would "calm the fury of this mad-bred flaw," whether the flaw in question is that a lower-born man is holding the sceptre, or that a less competent man is holding it. If he sees himself as a snake and a bringer of storms, he is perhaps honest in believing those poisonous and warlike images describe a fiercer and more effective England.

But there seems a stronger argument within these plays for the idea that possession is nine-tenths of legitimacy. In the latter part of Part 2 we get the faux-populist leader Jack Cade, spouting off about his own dubious claims to the throne and manifesting what is more or less Shakespeare's worst nightmare: rule by a mob, which is, like all Shakespearean mobs, easily swayed one way or the other by the slick speeches of whoever cares to woo them. Cade is in every way Henry's opposite; he is petty and bloodthirsty, and sends men to their death in a light, joking fashion. Not only is he an exaggerated caricature of the usurping spirit of the Duke of York himself, but he is actually acting on York's orders when he foments rebellion: not a ringing endorsement of the latter's fitness to wear the crown. Yet, despite Cade's obvious cruelty and nightmarishness for an anti-populist like Shakespeare, there is a fascinating grain of truth to his flippant, backwards speeches:

JACK CADE (to Lord Say)

Thou hast most traitorously corrupted the youth of the realm in erecting a grammar-school: and whereas, before, our forefathers had no other books but the score and the tally, thou hast caused printing to be used; and, contrary to the king, his crown, and dignity, thou has built a paper-mill. It will be proved to thy face that thou hast men about thee that usually talk of a noun and a verb, and such abominable words as no Christian ear can endure to hear. Thou hast appointed justices of the peace, to call poor men before them about matters they were not able to answer. Moreover, thou hast put them in prison; and because they could not read, thou hast hang'd them; when, indeed, only for that cause they have been most worthy to live.

This speech is undoubtedly funny, and undoubtedly horrifying for those of us who value the written word; at the same time, Cade's complaint about "justices of the peace [calling] poor men before them about matters they were not able to answer" rings uncomfortably true, at least in modern ears. It's not the last time Shakespeare used the comic relief of a lower-class character to take a pot-shot at issues of class or gender inequity, without stepping too far outside his own (and his patrons') received ideology.

A fascinating beginning; I'm looking forward to Part 3!

This looks wonderful - we're about to be off on a road trip, so I've printed this off to read to us as we drive!

Hope you enjoy, Jill! :-)

My husband and I both enjoyed the post. (I read it aloud to him in the car.) He is always delighted to hear examples of such erudite bloggers! :--)

I've been feeling a sudden Shakespeare craving as well. My son and I saw a production of Cymbeline--and odd little play that has be fascinated enough to want to read it. I kept wishing I knew more history of the time! And the two of us have tickets for Comedy of Errors next week on a very different stage.

"To calm the fury of this mad-bred flaw"? Amazing.

Cymbeline was one of Virginia Woolf's favorite Shakespeare pieces (and I am a huge Woolf fan), but I've never read or seen it! As is the case with a really surprising number of his plays. Always love to read and see a production in close proximity to one another, since I miss so much of the richness of the language while watching, but a read-through is lacking in character expression and interaction. I hope you and your son enjoy Comedy of Errors!

I just started reading Richard III (I watched the movie last week). I don't know much about the history or Shakespeare's versions of the history. But I really enjoyed reading this post. Sounds like I really need to read Henry VI after I've read this one -- I"m reading out of order.

Well, no matter what you do you'll always be reading them out of order in some way, since he didn't write the histories in the chronological order they occur...so no worries on that score. But I do think, having read & seen Richard III before but never the Henry VI plays before now, that they are enriching my understanding of what goes on in Richard - specifically this horrendous civil war that England has just been through, and everyone is so happy to have peace re-established, which makes Richard that much more of a villain for stirring it all up again. I'll be interested in your thoughts on Richard when you get around to it - it's a family favorite in my parents' house.

I read Henry VI a while ago, as part of my semi-suspended project to read all of Shakespeare's plays in order of when he wrote them, and I thought they were very silly for Shakespeare. I did like John Cade though.

Interesting, Jenny - I read your entries and I definitely agree that Part 2 is a lot stronger than Part 1. Which makes sense, given that this is the very beginning of his career. In particular the few moments of comic relief in Part 1 (like the scene when the Countess of Auvergne tries to seduce/take Lord Talbot prisoner) were oddly disconnected with the rest of the play, I thought, and yes - a lot of battles. And the section when Lord Talbot and his son are conversing in rhyming couplets for several pages did not work for me. Still, glad I got through Part 1 because Part 2 does pick up steam.

Great entry, sweetie! I don't know if it's the thesis or your Shakespeare-dependent lineage, but you really bring the depth in your reads of (forgive me - trying to avoid the "B" word) Big Willie's plays.

Thanks, Sweetie! It was fun to reconnect with that Shakespearean lineage with my folks over dinner last night, wasn't it? Much enthusiasm for shared viewings of Richard III and Much Ado About Nothing! Makes me excited to progress through the plays. :-)

I hardly ever have a craving for Shakespeare, but I almost always enjoy him when I do get around to reading him. To that end, thanks for a fine theater post and for celebrating a charismatic villain named Richard!

Thanks, Richard. The Duke of York is fairly charismatic, but just wait until Richard III - that's REALLY a charismatic Richard-ic villain!

The generally accepted position these days is that Shakespeare didn't write most of what we now call 'Henry VI'. (They were all first played with different titles.) Only the two scenes in which Henry actually appears are ascribed to WS and it's thought he probably added these at a later date so that the two plays he did write could be played as a trilogy after 'Henry V'. The first act is confidently ascribed to Thomas Nashe and the other four slightly less confidently to Thomas Kyd. Brian Vickers is doing a lot of work in this area at the moment and his papers are well worth the read.

Interesting, Annie - I'll check out Vickers.

Do you mean most of Part 1, or all three parts of what's now called Henry VI (since King Henry appears in many scenes throughout all three parts...)? If it's just Part 1 that would explain a lot about the difference in style & quality among the three...

Sorry, I didn't make that clear enough. Yes I meant Henry VI I. The generally accepted position now is that Shakespeare wrote the other two plays and the company with which he was working were having a real hit with them so Henslowe decided to cash in and got Nashe and Kyd to write what we would call a prequel to pull in the crowds. I would say Henslowe would have given the entrepreneur Lew Grade a run for his money, but perhaps only your UK readers would know what I meant:)

I've not read or seen acted the Henry VI plays and your review of 1 & 2 with both serious and funny bits is most enjoyable. Now I know what especially good reading I have to look forward to when the time comes to take these on.

Stephanie, Part 2 is definitely better reading than Part 1, but I enjoyed them both. It's fun to pick out the beginnings of Shakespearean themes starting to emerge. Then Part 3 gets kind of wacky...more on that later. :-)

I could do with a re-read of Hamlet. Heard somewhere that reading the whole thing in one sitting is a really awesome experience.

I did see it onstage in high school. Mostly I remember Ghost Dad going around in what appeared to be a clear plastic garbage bag.

Ah yes, the famous "Enter ghost, clad in garbage bag" stage direction.

Lear & Hamlet are probably the ones I'm most familiar with, from my thesis class. Still, I think I might be ready to revisit them before too long...