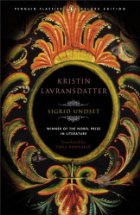

Thanks for dropping by the second installment of the Kristin Lavransdatter readalong, hosted by myself and, however reluctantly, Richard. :-) We'll be collecting everyone's responses to The Wife, Book Two in Sigrid Undset's 1920-22 trilogy.

Personally, The Wife was a bit of a mixed bag for me. The first 150 pages continued some of my least favorite aspects of The Wreath: guilt-ridden Christian moralizing, overwrought dramatic shenanigans from main characters, and seemingly ENDLESS weeping on the part of Kristin herself. Indeed, there's hardly a scene after Kristin's childhood in which she doesn't break down in tears for one reason or another. If she can't have what she wants, she cries. If she gets what she wanted, she feels guilty and cries. If nobody is paying attention to her, she cries some more. If she's the center of attention, she takes the opportunity to...cry. No wonder the woman loses weight throughout the book; between the tears and the alcohol consumption, she is probably severely dehydrated. After several hundred pages of listening to her whiny, guilt-stricken interior voice, my sympathy was wearing very thin. Like Lavrans, watching her weep at his bedside, I was continually asking "What is it now, Kristin?"

Kristin's inability to find peace for the sins of her early life is intensely annoying, but not unbelievable. I have to admit that I can relate to the experience of banging up against the same mental/emotional wall for years and years, making little headway, and even being alienatingly self-involved in the process. And a third of the book still remains for Kristin to come to terms with her demons. But what interests me about her spiritual block is how it reflects Undset's relationship to the church.

During the early scene when Kristin is walking twenty miles barefoot in sackcloth in order to be granted absolution by the Archbishop at Nidaros Cathedral (shown above, image courtesy of Flickr user Lisa Day), I thought to myself that, even if this kind of mentality seems harsh to me, belief in a Church hierarchy does at least provide a way out for believers who fall victim to sin. Kristin has to do this intense, painful penance, but after she's done it and the Church higher-ups tell her she's forgiven, she should feel at peace, right? That's one benefit of belonging to something like the medieval Catholic Church: someone else can theoretically decide for you when your sins have been purged, and then you get to start over with a clean slate.

But Kristin? Does not regain peace when the Church fathers have told her she's forgiven. She even weeps herself into two religious visions, and neither of them make much of a dent in her seemingly endless supply of self-recrimination. In some other book (James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, for example, in which Stephen Dedalus is hounded into complete abandon by his religious guilt), I might read this as a judgment of the Church - about how it's unrealistic to attempt to externalize shame, guilt, and forgiveness, or that any other human could know whether or not God has cleansed us of our sins. But it doesn't seem to me that Undset is taking this view. After all, she herself converted from skeptical agnosticism to Catholicism just 2-3 short years after this book was published, so she must have found some value in the structure and ritual it provided, even if, in her novel, it seems to act more as a crutch to prolong Kristin's self-flagellation, than as a comfort to mitigate it.

Most of the time I feel Undset is trying her best simply to present the medieval Norwegian Church: there are earnest, pious priests like Brother Edvin and Gunnulf Nikulaussøn, and there are also people who abuse their position in the hierarchy. Among the lay people, there are those who are victimized by the Church (men and women accused of witchcraft), and those who derive comfort and strength from it. But I continue to wonder about Undset's choice of protagonist - why focus on a character who seems, however pious, to be immune from the comforts offered by the Church - who seems actually to be made a WORSE person by her religiosity? Is Undset working out her own crisis of faith, just prior to conversion? Or is she merely making the point that spiritual journeys can be long and torturous? And why does Kristin have a more difficult time reconciling herself to her past mistakes than certain other characters do - her husband, for example? This is a question I often have about protagonists eaten up by religious guilt. Nobody around Stephen Dedalus seems to think they're going to Hell for a passing crush on a woman glimpsed on the streetcar, but he, for whatever reason, does. The priests have all told Kristin she has made amends for having sex before marriage, but she can't accept it. In both cases, the all-consuming guilt these characters feel erodes their ability to live their lives in a generous and responsible way.

What singles out these super-sensitive, selfish, all-or-nothing believers? A number of Stephen's behaviors (in particular his childhood bedtime ritual, which must be completed properly on pain of eternal damnation) align neatly with a modern diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder; Kristin, though, just seems depressed. One interesting parallel Stephen and Kristin DO share is an extremely close connection with their opposite-sex parent; Stephen spends Ulysses hallucinating his dead mother, and Kristin's relationship with Lavrans is a little too close for comfort. Is an overdeveloped religious fixation tied to some kind of Oedipus/Electra complex? Portrait and Kristin came out within four years of each other, around the time that Freud's theories were beginning to gain currency.

In any case, Kristin and her religious guilt do get to be a bit much. Yet around the 450-page mark (of the omnibus edition), I found myself enjoying the novel more than I had previously. Undset's narrative branches out, and we spend extended periods either outside Kristin's head completely, or observing through her eyes with minimal commentary. Whenever this happened, as in the narratives of Kristin's ex-fiancé Simon or Erlend's brother Gunnulf, I found myself relaxing into the storyline and enjoying the exploration of different corners of the medieval world, whether it be the hostels of Rome or the unconverted wilds of Finland. Occasionally, too, I started noticing moments when Undset made surprisingly poignant use of her plain, unadorned prose. This exchange between Lavrans and Ragnfrid, for example, struck me as lovely:

"Perhaps you may think, wife, that you've had more sorrow than joy with me; things did go wrong for us in some ways. And yet I think we have been faithful friends. And this is what I have thought: that afterwards we will meet again in such a manner that all the wrongs will no longer separate us; and the friendship that we had, God will build even stronger."

Something about the quietness of that "I think we have been faithful friends" is very touching to me, although it's marred by Ragnfrid's wish a few pages later that he had just hit her once in a while. Likewise, Kristin's slow realization of the depths of her parents' relationship, although it seemed a little, um, delayed (what is she here? in her mid-twenties?), struck a chord as well:

While she lived at Jørundgaard, she had never thought otherwise than that her parents' whole life and everything they did was for the sake of her and her sisters. Now she seemed to realize that great currents of both sorrow and joy had flowed between these two people, who had been given to each other in their youth by their fathers, without being asked. And she knew nothing of this except that they had departed from her life together. Now she understood that the lives of these two people had contained much more than love for their children. And yet that love had been strong and wide and unfathomably deep..."

By the end of The Wife I felt that the second book is stronger than the first, although still not a knockout. Despite an annoying protagonist, it widens its scope and develops a diversity of characters, and relies less on clichés of gothic and romantic literature than The Wreath. When she's not obsessing on her own sinfulness, Kristin can make an insightful observer, as when she contrasts the feasting styles of her husband and father, and notes that Erlend tends not to get as drunk or boisterous as Lavrans, since he's not as constrained while sober. I'm sure that the Black Death will give Kristin lots of opportunities to wail and sob, but I'm also somewhat hopeful for more non-Kristin time in Undset's third volume.

Visit others' posts:

- Amy enjoyed The Wife much less than The Wreath, due mostly to Kristin's unremitting sobs.

- Claire loved the setting but disliked the narrative voice, with which she never really connected. She also has qualms about the lack of forgiveness displayed by Kristin and the other characters.

- E.L. Fay continues her thoughtful exploration of the "anachronistic feminist," and argues that Kristin is convincingly embedded in her time - for better or worse.

- Gavin writes that she enjoyed the second book more than the first, particularly the setting and political intrigue, but that Kristin's weeping and religious guilt continues to bother her.

- Jill compares The Wife to Gone with the Wind, and notes that Kristin becomes less sympathetic while Erlend and Simon both become more so.

- Lena remarks that, while it was satisfying to see Kristin become a slightly more competent adult, her tears and vengefulness toward Erlend were less compelling. She remarks that the only character she ends up feeling close to is Simon.

- Richard finds Undset's narration style and content totally generic and uninteresting.

- Sarah, like so many of us, found Kristin's crying and nagging to be very unpleasant, and coins the phrase "epic nonsense."

- Softdrink wrote a pithy and amusing post highlighting Kristin's out-of-control fertility and her shrewish domestic stylings.

- Valerie enjoyed The Wife less than The Wreath, and continues in her opinion that Kristin Lavransdatter is male-centric. (For another interesting conversation about the novel's gender politics, check out the comments on Sarah's post!)